Along with skepticism about the pandemic’s seriousness, some rural Americans aren’t interested in getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO, HOST:

As the massive coronavirus vaccination effort has gotten underway, we’ve talked a lot about vaccine hesitancy, people who do not plan to take the coronavirus vaccine. Roughly a quarter of both white and Black Americans don’t plan to get the vaccine, according to the latest NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist survey. Thirty-seven percent of Latino respondents said they would not get the shot. White Republicans, though, are more vaccine-hesitant than any other group, with 49% of Republican men saying they do not plan on getting vaccinated. And rural residents were more likely to say that they don’t want the vaccine, too.

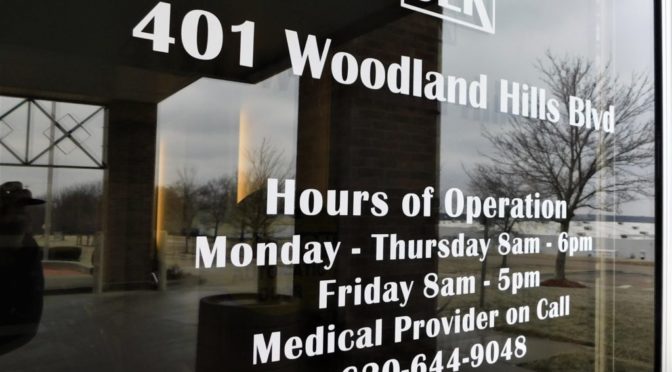

In the small town of Fort Scott, Kan., 1 in 11 people has been infected by the coronavirus. Even so, reporter Sarah Jane Tribble found some are still questioning how severe the virus really is.

SARAH JANE TRIBBLE, BYLINE: Seventy-year-old Linda Findley lives just outside of Fort Scott. She’s always been active in the community, helping with the Elks and fundraising. Like a lot of people here, she doesn’t think COVID-19 is that dangerous.

LINDA FINDLEY: I don’t even know what I think about it. I don’t know if I trust the testing if – because it’s so messed up or – I’ve had nieces and nephews that have it. I’ve lost good friends to it, or supposedly it’s to that. It seems like no matter what is…

TRIBBLE: Findley pauses to calm her two little dachshund dogs. They get excited when she’s on the phone.

FINDLEY: Everything seems to be coronavirus. I mean, it’s just – no matter what somebody has, it’s coronavirus. I don’t know whether it is or isn’t.

TRIBBLE: Her husband died about two years ago. Robert ran a popular auto body shop. He slipped on the ice and hit his head hard at the end of a workday. The emergency room, along with the hospital, had closed days before. Fort Scott is one of nearly 140 rural communities that have lost a hospital in the past decade. But not having a hospital doesn’t really come up when people here talk about COVID.

DAVE MARTIN: You know, when I got it, I was in good health, and it did take me a while to recover.

TRIBBLE: That’s Dave Martin. He’s the former city manager, and he’s pretty sure he caught COVID-19 at work last August.

MARTIN: I do remember waking up one of my bad nights and thinking – when I was running a temperature and not feeling very well. And I’m thinking, oh, wow, this could kill me – that I can get killed the next day, too. So it didn’t really stick with me.

TRIBBLE: After recovering, Martin went ahead with his retirement. He took his wife to Disney, and then they hiked Yellowstone. That casual disregard for the dangers of COVID worries health care leaders here.

Jason Wesco helps lead the regional clinic that took over primary care services when the hospital closed.

JASON WESCO: Me, my family – I think we are a significant minority. I think most people just keep doing – have maybe modified a little bit. Maybe they put on a mask in public. But I – the way I see it is I think life here has changed a lot less than it’s changed in D.C. And I think we’re seeing the impact of that, right?

TRIBBLE: Like much of rural America, the coronavirus skipped over Fort Scott last spring. But the pandemic hit hard in the fall, peaking in December. Across the county, two dozen have died from COVID, and most people know someone who had the virus and survived. But residents just seem tired of talking about it. And Findley says she won’t get the vaccine.

FINDLEY: How did they come up with a vaccine that quickly? And how do they even know for sure that it’s working?

TRIBBLE: The three vaccines approved by federal regulators in the U.S. are being given out to millions, and their efficacy has been shown through massive clinical trials in the U.S. and globally. But Linda’s skepticism isn’t unusual in southeastern Kansas, and that also concerns health leaders like Wesco of the Community Health Center.

WESCO: Yeah, I mean, yeah, there’s hesitancy. I’m sensing that it’s less. But I guess my point is when directly provided the opportunity to get it, it’s probably a different discussion when the vaccine is widely available.

TRIBBLE: Wesco says he’s hopeful attitudes are changing. His clinic has a waitlist for vaccines and is giving out as many doses as they can get their hands on.

I’m Sarah Jane Tribble.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: That reporting came from NPR’s partnership with Kaiser Health News.

Copyright © 2021 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.