MEXICO, Mo. — When the new corporate owners of two rural hospitals suddenly announced they would stop admitting patients one Friday in March, Kayla Schudel, a nurse, stood resolute in the nearly empty lobby of Audrain Community Hospital: “You’ll be seen; the ER is open.”

The hospital — with 40 beds and five clinics — typically saw 24 to 50 emergency room cases a day, treating patients from the surrounding 1,000-plus acre farms and tiny no-stoplight towns, she said. She wouldn’t abandon them.

A week later Noble Health had the final word: It locked the doors.

Noble, a three-year-old startup that acquired Audrain and nearby Callaway Community Hospital, offered explanations on social media, including “a technology issue” and a need to “restructure their operations” to keep the hospitals financially viable.

The company should have had plentiful resources to keep them afloat: Noble was launched in late 2019 by Nueterra Capital, a venture capital and private equity firm that has raised millions of dollars to back dozens of health care companies, according to Nueterra’s portfolio and federal filings.

What’s more, in addition to Medicare and Medicaid funds, Noble had received nearly $20 million in federal covid relief money in the 18 months before it closed the hospitals — funds whose use is still not fully accounted for.

Private equity investors, with their focus on buying cheap and reaping quick returns, are moving voraciously into the U.S. health care system; investments increased twentyfold from 2000 to 2018, and have only accelerated since. Financially distressed rural hospitals like Audrain are targets, putting vulnerable communities at the mercy of firms whose North Star is profit, rather than patient health. A recent report found that 441, more than 20%, were at risk of closing or losing services.

The saga that followed Noble into these towns may well serve as a warning flare from the rolling wheat and corn fields between Kansas City and St. Louis.

Noble acquired the hospitals after charming local leaders desperate to save beloved local institutions. And federal regulators did nothing to block or thoroughly vet the acquisition, despite red flags.

Noble’s directors had little health care experience. The one who did was Donald R. Peterson, whose previous foray into the space, an infusion company, ended with charges of Medicare fraud. Just months later, he became one of two directors of Noble, along with Nueterra’s chairman, Daniel R. Tasset, according to a state filing.

In an emailed response to questions from KHN, Peterson said the startup was meant to do good: “We created Noble to save a rural hospital that was about to close.” Tasset could not be reached for comment.

Audrain had struggled before Noble came calling, said Dr. Joe Corrado, a longtime surgeon at the hospital: On an average day in 2019, 40% of beds were empty, as more treatments moved to the outpatient setting and some patients drove an hour to larger hospitals for specialty care.

Things grew worse rather than better under the new private equity owners, according to Corrado as well as state and federal documents, gained through months of public records requests, and dozens of interviews with community leaders, health officials, and residents.

Once Noble owned Callaway and Audrain, the hospitals stopped paying their bills, according to lawsuits filed by contract nurses, security guards, and others. Inspection reports from the state workers coordinating with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services were alarming, listing 135 pages of deficiencies that put patients “at risk for their health and safety.”

Corrado saw his hospital being whittled away. Supplies for surgery disappeared, crucial medicines went unstocked, paychecks never came, he said. Just days before Noble suspended operations, he told management: “We don’t have the ability to do the things we need to take care of patients.”

When state health department surveyors arrived at the Callaway hospital in late summer 2021, only three patients remained, all in the geriatric psychiatry unit.

Inspectors reported they witnessed a suicidal 77-year-old stab her own leg with an ink pen, that an 85-year-old missed his medicine over the weekend because a pharmacist was unavailable, and that nurses waited five minutes to provide oxygen after surgery because the machine malfunctioned.

Ambar La Forgia, a Columbia University assistant professor who studies private equity in health care, said the business model, in general, is “all about creating short-term returns for shareholders.” The emphasis on profit, she said, is “not necessarily great for the patient.”

That, La Forgia said, raises hard questions for rural America: “Is a bad hospital better than no hospital?” And how should federal regulators who approve hospital purchases and monitor their performance thread that needle?

Hospitals Hollowed Out of Drugs, Supplies, and Salaries

Audrain was once a 247-bed regional destination for care, with more than 4,300 admissions in 1992, according to a county bond report. Internal medicine doctors, orthopedic surgeons, and pulmonologists competed to admit the most patients.

By 2019 it was a shadow of that former self. Yet patients like Dee Tate, diagnosed with cancer in 2020, relied on it. She got blood tests, scans, port placement, and chemotherapy to put her into remission — all at Audrain.

So she was shocked when her oncologist, Dr. Shahid Waheed, told Tate he couldn’t perform her scheduled infusion this January.

“If I don’t take this treatment, the likeliness of this kind of cancer coming back goes way, way up,” she said.

The medication, Rituxan, was not in short supply nationally. Noble could not stock it because the hospital purchasing department did not have the money for it, according to a former hospital employee who spoke on condition of anonymity. Ultimately, the person said, the staff bought it directly from the supplier.

Tate’s infusion was five weeks late. “It came from Indiana,” she recalled. Tate, along with about 500 other patients, now must travel at least 40 miles for cancer care.

In the operating suite, Corrado said he could never be sure supplies like anesthesia medicines, bandages, and catheters would be available for surgeries, from mastectomies to emergency appendectomies.

Management determined who would be paid on a week-by-week basis, he said: “On one Friday, they would pay the employees, and they couldn’t buy anything else. And another week they would be able to maybe buy supplies.”

Money troubles were not new to the hospitals. Despite federal subsidies, rural hospitals often struggle because their patients tend to be on Medicare or Medicaid or have no insurance, providing less revenue than commercial insurance.

The year before Noble bought Audrain, the hospital reported an $18 million loss for patient services on $44 million in patient revenue. The Callaway hospital had eked out a $170,000 profit from patient care while still owned and operated by Nueterra.

The next year, under Noble’s management, Callaway reported a nearly $6 million loss on patient services, its 2020 Medicare cost report showed. On paper, financial filings show, it had spent 43% more than the year before.

But much of the money was not spent on delivering health care, said Ge Bai, a professor of accounting at Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, who reviewed Callaway’s most recent Medicare cost reports for KHN. She noted that the hospital received millions in covid relief that it reported as miscellaneous income.

The hospital’s spending on laboratory, medical supplies, contract nursing, and care all increased, as is expected in a pandemic, Bai said. But she questioned other line-item cost increases.

For example, spending on the non-salaried employee benefits climbed 273%, to $1.4 million. Callaway’s 18-bed hospital nearly doubled its spending on administration, adding $1.1 million in fees paid to Nueterra subsidiaries NueHealth and Noble in 2020. The hospital also paid Noble a $38,000 lease in 2020, a statement filed with Callaway County showed.

“These dramatic increases raise a red flag,” Bai said. “To whom did the money go?”

Noble executives repeatedly declined requests for comment or interviews to clarify such questions. In late March, Noble spokesperson Nancy Mays said they did not have time to answer questions because they were “talking to potential buyers and figuring out how to best serve employees right now.”

A Sales Pitch Heavy on Charm

Audrain County officials were easy prey for investors. Noble was the only bidder for the failing hospital, said Lou Leonatti, the longtime local attorney, and many in Mexico, a town of 11,000 and the county seat, “believed we were saved.”

Dana Keller, the head of Mexico’s Chamber of Commerce who felt a hospital was essential to keeping business in town, said she set up meetings so Noble’s executives could “talk about their philosophy for rural health care.”

Leaders who called themselves “Progress Mexico” tried to evaluate the startup. “At the time we looked at it, Nueterra had an ownership interest, Don Peterson had an ownership interest, Drew Solomon, and Tom Carter,” Leonatti said.

But there was much they didn’t know or overlooked. None of Noble’s three founding owners had run a hospital or navigated its regulatory demands. Only Peterson — a serial entrepreneur who spent decades investing in workstation and information technology businesses — had worked briefly in health care, and that ended badly.

In 2012, he created IVXpress, now called IVX Health, with infusion centers in 10 states. Peterson left IVX in 2018 after a whistleblower accused him of altering claims, faking drug purchases, and paying a doctor kickbacks. Peterson settled the resulting Medicare fraud charges with the U.S. Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General without admitting wrongdoing.

Such OIG settlements are “in essence the federal government saying that we don’t trust you,” said Robert Salcido, an attorney who specializes in health care fraud.

Jeff Morris, Peterson’s attorney, said in a letter to KHN: Peterson’s five-year voluntary “exclusion applies to health care programs only, this precludes him from making any claim to funds allocated by federal health care programs for services — including administrative and management services — ordered, prescribed or furnished by Mr. Peterson.”

Morris said Peterson had been “diligent in complying with his exclusion,” which began Aug. 5, 2019. Peterson agreed to pay $334,800 in restitution. According to the terms, violating the agreement could bring criminal prosecution and as much as $4.5 million in penalties.

Within months of the settlement, Peterson signed Noble’s filing to register in Missouri as a director — as well as its secretary, vice president, and assistant treasurer. In April 2020, he ordered medical supplies for the Callaway hospital, according to a receipt obtained through a public records request.

Pandemic Relief and Unpaid Bills

As in much of rural America, the pandemic was slow to emerge in Callaway and Audrain counties, but covid-19 cases were climbing by fall 2020. The hospitals hired contract nurses for help and when possible transferred patients to larger, urban areas.

Callaway saw a surge in late 2020 and closed its general inpatient care in January 2021. Audrain, the larger hospital, dealt with a surge of daily cases in that span.

Noble pursued all forms of coronavirus-related funding. On its watch, Callaway and Audrain hospitals attested to receiving about $11 million in federal relief, which rolled out after the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act was enacted in March 2020. Noble’s hospitals also took in $4.8 million in loans from the federal Paycheck Protection Program that have been forgiven.

Hospital cost reports from 2020 indicate that the millions should have helped: Audrain’s health care staffing costs were $3.5 million, and Callaway’s were $562,000.

Noble also turned to state and local officials. Missouri distributed $1.1 million to Noble from its CARES funding, mostly to Callaway for covid testing.

Callaway County drew from two of its own federal allocations for the hospital. As of February, leaders had approved more than $14,000 for covid testing, funded by the American Rescue Plan Act. In addition, invoices provided through a public records request show that the county used CARES Act funding to pay Noble’s hospital nearly $364,000 for covid testing, operations, and marketing.

Noble sought Audrain County’s help last fall to pay contract nurses after pandemic costs soared. Its commissioners approved a one-year $1.8 million loan using ARPA money. The loan is due in September, at a 2.5% interest rate. If Noble defaults, the rate climbs to 5%.

Even as the hospitals looked flush with federal money, contractors were pulling out, according to lawsuits that allege more than $2 million in unpaid bills.

In one suit filed April 21, Moberly Anesthesia Associates said the Audrain hospital failed to pay nearly $214,000 for services provided.

Among other lawsuits:

- Sodexo Operations, a food services provider, signed a contract with Noble Audrain in May 2021 and filed suit in January, saying it is owed more than $555,000.

- Contract agency Grace Staffing pulled its nurses from Callaway’s ER and other floors last year, saying it is owed more than $125,000.

- PTC Laboratories, in Columbia, Missouri, said Noble owes more than $500,000 in back payments and late fees for thousands of covid tests of Callaway employees.

Noble Health executives Carter and Solomon declined to comment on the lawsuits.

Nueterra Capital CEO Jeremy Tasset, the son of Daniel Tasset, said in a March email that “we are a minority investor in the real estate and have nothing to do with the operations of the hospitals.”

Callaway County records show Noble owes more than $72,000 in unpaid property taxes and penalties.

Audrain and Callaway counties’ records confirm that Noble kept hospital operations and real estate assets separate — a common move, experts said, from the private equity playbook, when profits are expected from property value rather than medicine.

Said Rosemary Batt, a management professor at Cornell University: “That’s a tipoff that they must be doing something to monetize the real estate to make money.”

Patients ‘At Risk for Their Health and Safety’

Eileen O’Grady, research manager at the nonprofit Private Equity Stakeholder Project, said private equity’s focus on strong, speedy returns makes it a risky business model for health care. “In rural hospitals,” O’Grady said, “there are very few ways” to boost revenue and cut expenses “without having an impact on patient care.”

Indeed, by late summer 2021, federal and state inspectors found alarming deficiencies at the Callaway hospital and gave Noble 23 days to fix them.

Noble took some corrective actions, so inspectors cleared the hospital to admit patients and receive funding. But it was not exactly a clean bill of health.

The September checklist of deficiencies spanned 16 pages, compared with 135 the month before. Some lapses, such as not staffing an overnight ER doctor, were unaddressed.

At the Audrain hospital, inspectors found “ineffective management.” Its electronic medical record system did not keep patient information. Its behavioral health staff did not retain records or footage of an alleged patient assault, and inspectors found long electrical cords next to beds, a risk for strangulation.

Meanwhile, the three men who ran Noble were shopping for more hospitals to buy.

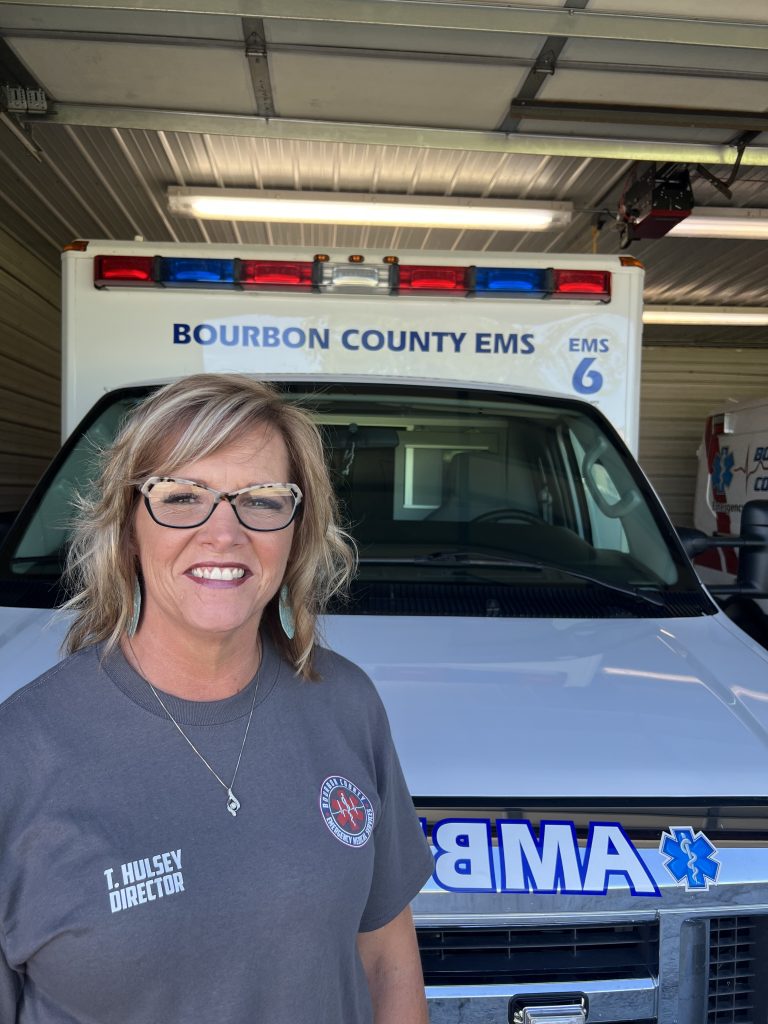

Solomon and Carter pitched Noble’s services to officials in Fort Scott, Kansas, whose hospital had closed in 2018. City and county leaders on July 23, 2021, paid $1 million from their American Rescue Plan Act funds for Noble to study the feasibility of reopening. The money was paid to a new company Peterson founded in June, Access Medical Advisors.

Solomon, president of Noble’s real estate company, told the county in late March of an “incredible” finding from the study — Fort Scott’s hospital building was worth $19.6 million, which “could present the borrowing basis or the bonding basis for a really great viable community project to move forward.”

Solomon’s discovery came as Noble’s hospitals in Missouri remained closed, staffers looked for new jobs, and patients traveled even farther for care.

It came as Noble Health appeared to be unraveling. In late March and April, the Kansas City attorney who registered the company, its hospitals, its real estate entities, and Access Medical Advisors — Philip Krause — informed state officials he had resigned his positions with all of them.

Peterson’s LinkedIn page said he has retired from Noble Health. In March he incorporated a new company, Noble Health Services, based at his home address — a half-million-dollar brick colonial in a leafy Kansas City suburb. Its purpose: “healthcare administrative services.”

As for Noble’s failed hospitals, Texas-based Platinum Team Management executive Cory Countryman said it would buy and reopen them. “We have equity investors,” said his colleague Melissa Upshaw, as well as “traditional financing” and “a portfolio of our own.” Countryman does have recent health care experience: In 2017, as CEO, he abruptly shut down Walnut Hill hospital in Dallas.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.